In the time before everything" curated by Paula Varjack Photo by Ben Gregory

This article by London-based writer, poet, performer and educator Keith Jarrett is part of the Spread the Word series, commissioned for the SLG’s Convergence programme.

Intention is a word I’ve been coming back to of late.

In my youth, my resistance to galleries could be located in my discomfort at not being the intended audience, of feeling excluded from the cultural conversation. As a writer, I can now revel in this unintention, and employ it as an element of creative exploration.

While researching a painting of Patrick Nelson, a queer Jamaican who settled in Britain during the interwar period, I became acquainted with Gemma Romain, a historian and academic who advocates reading ‘against the grain’. Her painstaking archival work showed how events captured and captioned with one intent can hold significance for other purposes, sometimes at complete odds with the original one. ‘Against the grain’, to clarify, does not denote inscribing previously held ideas onto artefacts, but approaching them against the original intention. The letters, court documents and army records kept for official purposes that Romain examines make only passing reference to her subject of interest. The abandoned sketches are captioned with misspelled names. Both hold creative potential, a speculative door.

Words and images from the past, with a retrospective glance, can acquire greater depth, greater poignancy. While the term ‘queering’ subjectivity has come to stand in as an idea for any attempt at reconfiguring standard approaches – at least in academic discourse – there is some merit in contesting the expected and the normative to construct art and to question status quos.

It is with this in mind – sort of – that I come to Paula Varjack’s latest work The Time Before Everything. What happens when, as artists, we reframe our own recent histories, when we begin to assess the crises we are currently experiencing with a backward glance?

From In the time before everything. Curated by Paula Varjak. Image credit: Benjamin Gregory

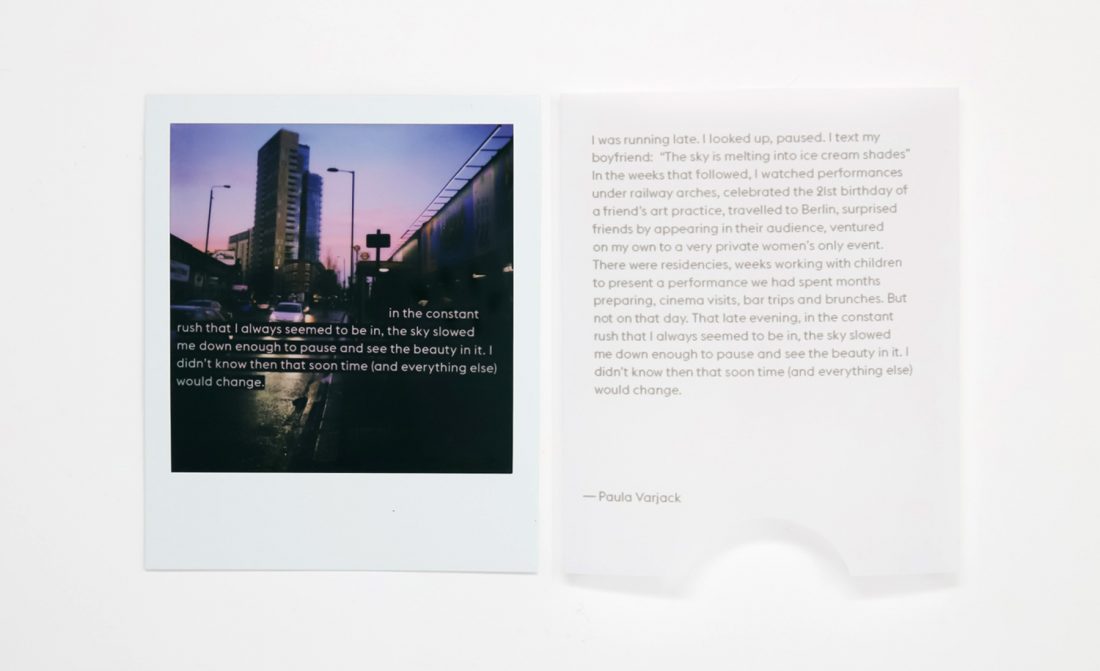

In The Time Before Everything, Varjack utilises images by twenty artists, captured on phone cameras, shortly before the first UK lockdown in March 2020. These were impulsive snapshots, taken with limited curatorial ‘knowingness’; they were not originally intended to hold any cultural or historical meaning, aside from eliciting immediate responses on social media. By converting them to Polaroids and inserting them into caption sleeves, the ephemeral is reconfigured as a commemorative article.

By way of exploring more of these themes – of intention, inclusion, exploration – I spoke with Paula, whom I first came to know through the spoken word poetry scene and other subversive happenings such as the Anti-Slam, where deliberately bad poems are performed. In many ways, this feels like the continuation of a conversation about the merging of visual, performative and literary expression, one that we have conducted both publicly and amongst other friends and colleagues.

From In the time before everything. Curated by Paula Varjak. Image credit: Benjamin Gregory

From In the time before everything. Curated by Paula Varjak. Image credit: Benjamin Gregory

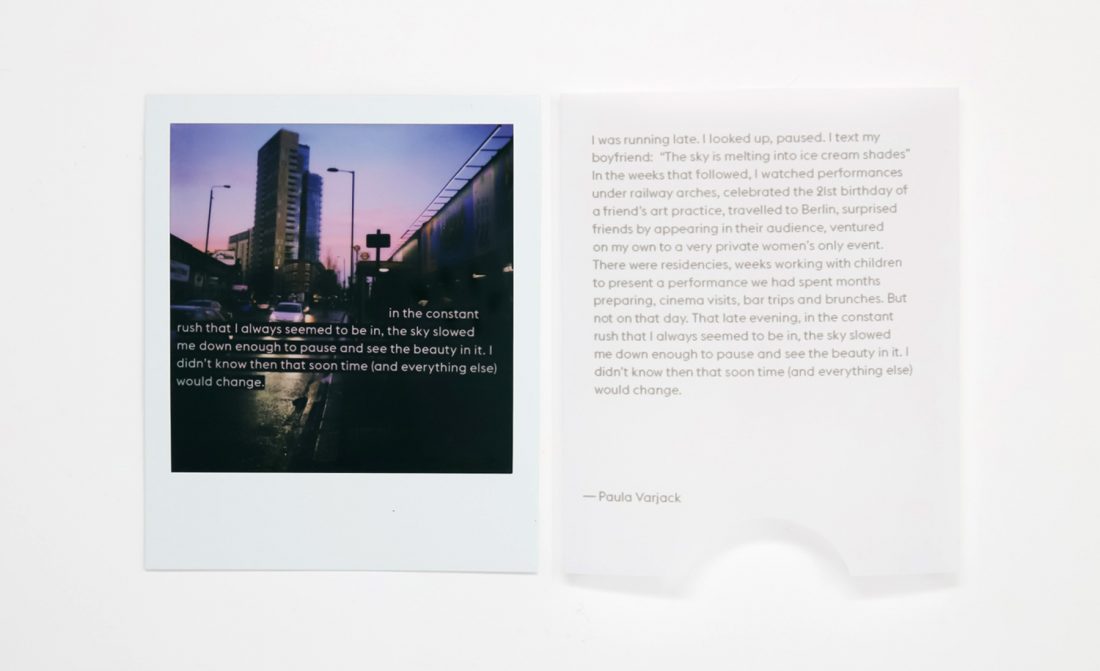

KJ: Looking at your own Polaroid, I’m struck by the light and shadow, the in-betweenness of night and day. The car lights are on, the streetlamps are not. Your caption alerts me to the sky’s beauty, the pinks and blues it holds: ‘The sky slowed me down just enough…’. And yet, the gaze is drawn to the tower cutting through it, almost as if it were part of the sky. The sharp lines all point towards this off-centre island where the tower sits, and in front of it, the humbler red brick building and a skeleton tree.

And perhaps I’m reading too much into it, but there’s something unsettling about it. Perhaps it’s the liminality of the time. Perhaps it’s the squashedness of the pavement, containing Bus Stop K, two-way pedestrian traffic and the shop fronts, given a year’s worth of social distancing. And perhaps I’m bringing my own baggage into the mix when I think about in-betweenness, and how I imagine Shoreditch as a tourist’s vision of ‘East’ London, glitzier than the further Easts I’ve grown up in, how I see it as a doorway opening towards my suburban roots. But, more than anything, in this image, I’m drawn to the city structures: the concrete, the brick, the street furniture, the matching Uber cars…

Could you say more about the urban landscape for you, and how it frames your work?

PV: Cities are one of my greatest inspirations in making work. My relationships with cities are like romantic ones: long and short term, infatuations, crushes, affairs, sudden and slow burns. Due to life circumstances, I’ve spent much of last year in the countryside. Over time I have come to appreciate it, but up until now it is urban landscapes that make me thrive. I love architecture, and culture, and people. I love how different communities and time periods can visually seem in conversation with each other. I can try to explain and contextualise but to be honest I think it’s something that is just in me. I also grew up in the suburbs, but my very earliest memories were about this deep desire to live in the city. It’s a source of endless inspiration, a living collection of stories and life constantly happening.

From In the time before everything. Curated by Paula Varjak. Image credit: Benjamin Gregory

KJ: What was the process like for you of returning to your impulsive image and narrating it?

PV: The funny thing about the image I chose, is in a way it was already narrated. It was taken on the 16 February. I posted it to Instagram the night after with a throwaway caption. What was notable for me then was the sunset.

Seeing it, I remember the night so clearly. I had been to London Fashion week and was rushing to meet friends to see a film at Rich Mix. I remember running out of an event and onto a packed tube, rushing down the pavement to just make it time for the cinema. I stopped to take the picture when I should have arrived ten minutes earlier, but that brief pause to capture it felt important. When I looked through my photos of that period, this image brought it flooding back.

But even the memory, of rushing from one part of London to another, from one event to another, it’s only notable because of how much different time now feels. The photograph is a moment in time, but now with the lens of reflection it is somehow a different moment in time. This is part of what I love so much about the layers of the piece and inviting others to be part of it.

The different stages of the process in creating individual Polaroids for In The Time Before Everything are all doing something different to time, and the memory. There’s the moment someone decided to take the photo on their phone, the moment they are looking through their photos to decide which photo to submit to the project, the story they then tell looking back at that photo, the developing of the photo onto Polaroid and then the encasing in the text sleeve. I really love the idea then of the person who receives the box of Polaroids and how they interact with them. Do they want to display the Polaroid and remove it from its story? Or protect it in this narrative sleeve?

KJ: In some ways, the juxtaposing of text and image creates a tension between what we see and how we interpret it. Returning to the original ‘throwaway’ narration, and then rewriting it through the lens of a year’s reflection challenges our gaze, and so in some ways, to me, it feels to me more like a literary endeavour, even though the image remains the centrepiece, whether encased or let loose.

How does literature – how do words – inform your visual art more generally?

PV: As someone who creates with a love of stories and cinematic imagery, it’s probably not surprising that I am often finding ways to play with text and image and text in dialogue with image. Or maybe I just like playing with different forms to tell stories. As much as I work and have worked with words though, I do think I am far more often led by images. So I guess it might be more accurate to say that everything I make is led from the visual, but that the form it then takes could be text or film or performance or whatever. It’s also funny for me to think of myself as making “visual art” even though I often work in visual media like video. In terms of what informs my work, I think I am endlessly fascinated by the cultural dialogue created and responded to by pop culture. That probably has a bigger impact on what I make then anything defined as literature.

Image credit: Benjamin Gregory

KJ: It feels like the last year has prompted a degree of self-reflection for artists, both on a personal level and also in terms of the wider creative industry. It also strikes me that much of your work already invites those of us who engage with it to consider our positions, whether as artists in an inequitable system, or consumers of fashion, or slam poets, and so on. How much are you driven by the inward gaze and why is it important to confront this in your work?

PV: I think that reflection is always a central element to my practice. It might be partly due to being an only child, comfortable with spending a lot of time on my own, and partly due to being drawn to narration in novels and films from an early age. I think there is something in this, though, that is also about audience, creating something and from the very outset thinking about audience, thinking about presenting the thing you are making and what you would say. And maybe there is also a connection to my love of interview, so even with myself there is always this question of why, why did I make that/ capture that/ what does it mean? Why do I want someone else to notice it?

KJ: I’m also thinking a lot about playfulness and joy, which sometimes feel at odds with introspection. At this moment when the gaze moves inwards, we tend towards solemnity and lose our playfulness. What does play mean to you now?

PV: I think the role of play is absolutely essential in pretty much everything, but especially in the creation of art and in the nature of experiment. You can only feel free to fully explore something when you allow for an element of play. Play is about a joyful exploration of something, about allowing for surprise and even mistake to take place. I also feel by not taking something too seriously you can free up a lot of creative energy. The idea of game and gamifying is also interesting to me: what happens when I set parameters for someone else that I invite to play?

KJ: Yes, the invitation is key here. And whilst your chosen image is the springboard for our conversation, I’m aware of the other artists you’ve connected with for this piece. At least for me, as a poet and fiction writer, inviting peers to share the chaotic process of articulating a thing to the outside world seems a daunting prospect. I get the impression that this synergetic process is an energising one for you. How can we all find meaningful ways to interact as artists without losing ourselves in the process?

PV: I spent a lot of my artistic career defined as a solo artist, but the funny thing about that for me is that, even when making solo works, in the lead up to finishing a project, a lot of collaboration took place: sharing versions of stories, poems, short films or cabaret numbers for feedback, for example, or working with creative teams to support my solo projects. Maybe there is something that comes from my film training, all the different voices and roles that can fulfil what comes to feel like singular vision.

I think collaboration is often about being clear about what you gain from working for others and articulating why and how you want to work with them, and then opening yourself up to what happens. I think there can then be a balancing act between continually checking in with yourself as to what you want but allowing the work to have its own voice too, to let it tell you what it needs to take place.

Thank you!

ABOUT

Keith Jarrett is a writer, poet, performer and educator based in London. He is. UK Poetry Slam Champion and FLUPP International Poetry Slam Winner. His Poem, ‘From the Log Book’, was projected onto the façade of St. Paul’s Cathedral and broadcast as a commemorative art installation, Where Light Falls, in 2019. His play, Safest Spot in Town, was performed at the Old Vic and aired on BBC Four. Selah, his debut poetry collection, was published in 2017 by Burning Eye Books.

Keith was selected as one of Val McDermid’s ten outstanding LGBTQI+ writers in the UK for the International Literary Showcase. He has judged the Polari Prize, the Foyle Young Poets Award, and is the Europe and Canada regional judge for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize 2021. Having recently completed his PhD at Birkbeck University, he is finishing his first novel and teaches on the Creative Writing MA.

Paula Varjack is an artist working in performance, video and participation. She makes work as a way of making sense of and communicating with the world. In every show she makes, she aims to find the balance between making audiences question themselves, and feeling like they have had a fun night out. She uses storytelling to take audiences on a journey, shining light on what some might find uncomfortable, or may not have contemplated before. She is a London Pleasance associate artist and a Barbican Open Lab artist. She has been commissioned to make work by The Barbican, Battersea Arts Centre, Camden People’s Theatre, Fuel, The Marlborough, Attenborough Centre for the Arts, Upstart Theatre, Beam, and First Draft Cabaret.

She is the creator of the Anti-Slam a satirical take on Poetry Slams where the lowest score wins. In addition to creating, she facilitates writing and performance workshops with a wide range of age groups, and mentors emerging artists on developing their creative practice. Born in Washington D.C. to a Ghanaian mother and a British father, out of many places she has lived she considers east London to be “home”.

Spread the Word is London’s writer development agency, a charity and a National Portfolio client of Arts Council England. It is funded to help London’s writers make their mark on the page, the screen and in the world and build strategic partnerships to foster a literature ecology which reflects the cultural diversity of contemporary Britain. Spread the Word has a national and international reputation for initiating change-making research and developing programmes for writers that have equity and social justice at their heart. In 2020 it launched Rethinking ‘Diversity’ in Publishing by Dr Anamik Saha and Dr Sandra van Lente, Goldsmiths, University of London, in partnership with The Bookseller and Words of Colour. Spread the Word’s programmes include: the Young People’s Laureate for London, the London Writers Awards and the national Life Writing Prize.

Convergence is an ongoing series of critical conversations, screenings and written commissions, facilitated by the SLG and curated and hosted by invited guests.

With Art Fund support