Film still: Mandabi (1968)

A reflection on Black/African cinema through four films.

Director Alain Gomis speaks of cinema as the realm where we encounter ourselves within the specific experiences of others. His decision to focus on specificity speaks to the political aims of what we call African and Black cinema. Specificity resists forms of historical and present-day neo(colonialism). Imperialism in cinema, as an art form and industry, often confines themes and aesthetics to misery and exoticism. Black/African cinema works to transform the imperialist impulses of the lens into an instrument that affirms and defines African and diasporic culture and language as something distinct.

There is a motive amongst filmmakers of African descent to extend beyond location into personhood. In Tey (2012) by Gomis, we experience the character Satchè’s last day on earth. In the morning, his eyes blink open as if emerging from the primordial womb. As the day progresses, these eyes are interchangeable with an astutely choreographed lens that weaves, propels and lingers on farewells to city streets and lovers. Death looms fast and slow towards the end of the day. In the mundane confines of his domestic compound, time moves slowly enough to capture grief, unfurling into contentment. By dusk, it accelerates into a luxurious time-lapse to old age. Is this a day or a lifetime lived as a day? The innate mysticism of Satchè’s predicament is not just confirmation of a repressed long-forgotten spirituality. The mysticism also hints at sonder, the realisation that each person is living a life as vivid and complex as your own. Mysticism bridges the gap between Satchè’s vivid reality and the outer world. For Gomis, there is no question about the realities of an external world we share and labour within. What is also true is that the repercussions of the exterior world play out for us almost entirely within. We spend most of our time there.

The decision to focus on the personal might lead to assertions of apolitical humanism. Particularly at a time in media culture where the politics of representation are being used as a placeholder for the political urgencies that circle Black life. Gomis’ highlights how politics play out in Satchè’s dimming world. His near muteness speaks to sobering death while emphasising his backstory as a returnee. An expressly diasporic condition where an individual who returns to the continent after living or studying abroad reinhabits their natal home with the sensorial experience similar to a visitor.

Seeing through rather than looking at creates an intrigue in what we see, without the obligation to define or affirm. Political urgency transforms into political resonance, offering a far richer sense of place. The infinite mix of inner and outer experience make it impossible to be limited by an essential world. The refusal of these limits reoccurs in cinema from the Black Atlantic from Dakar streets to estates and dancehalls in Harlesden.

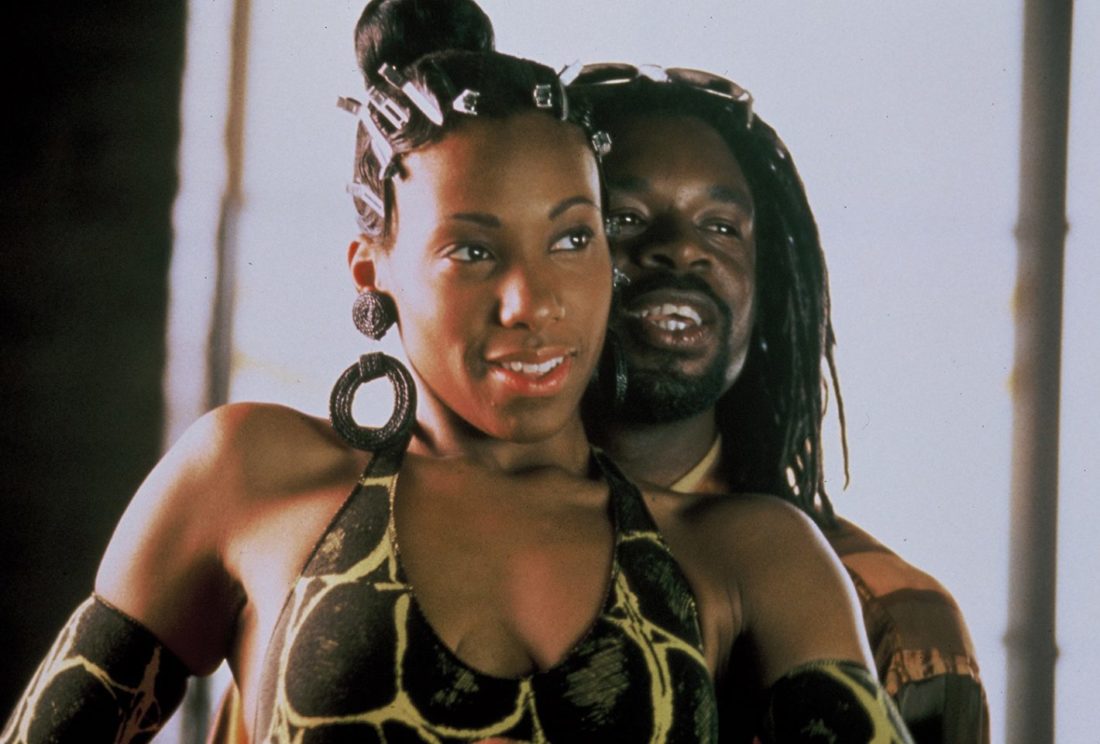

In Babymother (1998), the musical playfully distorts the need for social realism to mine the realities of worlds and the people in them that we think we know. Through the young mother, Anita’s quest to self-actualise through dancehall fame, we see a Black Britain more clearly. Musical performance bridges the film locations: concrete stairwells, snooker halls and clubs are filled with a life force that exceeds the experience of marginality and erasure. Realism is rooted and, at the same time, Fantasmic. It is not a question about what African or Black cinema is, but what it does.

Sembene’s Mandabi (1968) simply, or deceptively so, invites other ways of looking. The film follows Ibrahima, an illiterate man without identification papers attempting to navigate the layers of Senegalese bureaucracy necessary to cash a money order sent from his nephew Abdou in Paris. Mandabi raises questions about where the Africa fought for and imagined exists in newly independent nations. The effort taken to render the intonations of language and traditional forms of kinship honour tradition, while placing them into a dialectic with citizenship requirements. From this clash a third way or blended culture, with all its diverse elements and influences, emerges. A return to any particular state, be it pre-capture or capture, is unlikely. As much as he suffers under bureaucratic erasure, Ibrahima is also a victim of pride. His industrious wives and neighbours are somehow able to maintain communal roles whilst staying aware of national requirements. Ibrahima’s naïve faithfulness to a fading social structure contributes to his ruin.

The earliest examples of Black African cinema show that cultural shifting and blending are an essential part of the pan-African narrative. In Mandabi, the implications of Abdou’s migration to Paris are an absent presence that animates the story. Abdou represents cultural dynamics and exchanges to come. In Paris, a forthcoming diaspora, and at home a reliance on diasporic capital, that will alter the trajectory of development. What we need to bring to our engagement with Africa, as a concept, locale or cinema is an understanding that it exists as a container for shifting realities.

The central character in Film Festival Film (2019), Fanon, nervously paces the length of her room on the tenth floor of a Durban hotel. The sound of crashing waves from an open window obscures her inner monologue, as she rehearses the contortions necessary to pitch her debut feature to the international market. Directed by the Medu African Film Ensemble, the film holds the problems and proposes solutions to questions about (African) cinema and who gets to make it. By refusing to conform to the tenants of fiction and documentary, the filmmaker-subjects free themselves from having to perform or collude with a restrictive reality. For Medu, it is the hermetically sealed world of film festivals where creative ingenuity clashes with hyper-capitalism and bias. In posing as a film-crew-within-the-film, with their supporting cast of real “leading, industry professionals”, Medu ask critical questions of themselves as their peers. It is impossible for them to hide behind the camera when conversations about race, gender and economics are being held. In actively participating in their reality, they exceed the limitations of the festival and funding models by making the film itself. In the end, Fanon never makes the pitch. Her nervousness is not a resignation to conformity. It is a movement towards self-belief and the possibility of another way.

Tega Okiti was the curator for South by South for 2021. South by South is a quarterly film screening at the South London Gallery. The programme focuses on presenting bold and innovative cinema from Africa and the diaspora to audiences in the UK.

Explore our upcoming film screening events and book your ticket to the next one today.

Still from Babymother, 1998. Photo: Colin Patterson